Roots in Revolution

Originally published on 26th August 2023

Knowing Quakerism’s origins is one important key to appreciating part of its essential nature. Quakerism has its roots in revolution, and a fascinating history of challenging authority and speaking truth to power.

If you‘re curious about Quakers, I want to tell you more about where Quakerism comes from.

Quakerism springs to life back in 17th century Britain around the time of the English Civil War. This was a period of political instability and dramatic societal change. Not only was the governing system of the monarchy and parliament convulsing, the printing press and growing literacy were disrupting the control of information. Power was in flux and radical ideas about how society might be more equitably organised were igniting people's hopes and imaginations.

In this brief time of possibility and upending social order Quakerism emerged.

The Protestant Reformation had come to Great Britain roughly one hundred years before, and had broken the monopoly on religion and power the Catholic Church had enjoyed over the previous thousand years. Religious authority had shifted, from Rome and the Pope to the Bible. Quakers and other like minded groups of the time would seek to shift it further.

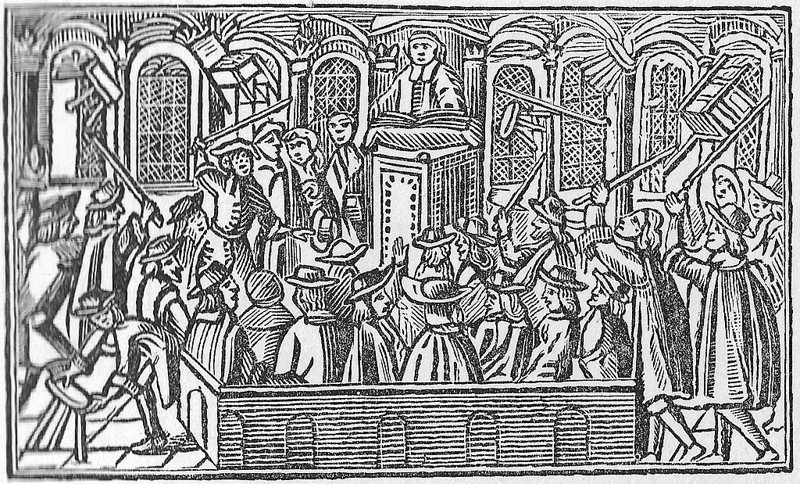

Amongst Quakers, George Fox, the founder of the movement, is known for many things. One of them is standing up during a church service, interrupting the minister’s sermon, and saying to him: You will say Christ said this, and the Apostles say that, but what can you say?

What can you say?

It was about shifting the centre of authority even further: this time from an authoritative interpretation of the Bible and the significance of events of the past, and especially from people privileged and educated to interpret them, to the lived experience and connection to the divine available to the individual — any individual — seeking spiritual insight and a connection to God in the present.

It was a dramatic and public challenge to the exclusive authority of the minister and the church to say what is divine, inspiring others who were there in attendance — most notably an incredible woman named Margaret Fell, who would become central to the growth of Quakerism.

But it also remains a challenge for each of us to this day: What can we say? What can we say from a place of truth about our lives and the world we are part of? To borrow from the great American poet Walt Whitman, himself inspired by Quaker thought: What verse can we contribute to this powerful play of life?

George Fox is considered central to the founding of Quakerism, but he is not seen as a messiah, nor did he see himself that way. In speaking out, Fox was defying the authority of the priest. He was openly questioning the basis for that position of authority. And he was disputing whether this privileged person was speaking honestly, from any personal knowledge or direct experience.

It was a bold, radical act, and Fox and other early Quakers were imprisoned, tortured and worse for their bravery in trying to confront the failings and injustices of the world they were living in, to make it a better, more free and fair place. They began a tradition of spiritually-rooted activism that continues for Quakers to this day.

Fox, Fell and the early Quakers had found that they didn’t need a book or a church, a degree or especially a priest to form a relationship with God. Instead, through their spiritual experimentation they found that if they were able to centre themselves in stillness, they could become connected to and moved by a force inside themselves and amongst each other. They gave different names to this eternal force they experienced — the Inner Light, the Seed, the Source and yes, God, the Holy Spirit and also Christ Jesus — but names and words were beside the point. What was important was the experience in the moment, the insights it offered and the changes it brought to these people’s lives.

In grounding themselves in an inclusive, egalitarian spiritual practice (what‘s now known as Quaker Meeting) and resisting both dogma and hierarchy, these early Quakers birthed a uniquely pluralistic and perennialist religious tradition all the way back in pre-industrial, agrarian Britain. Their free and open worship grounded in a belief in the equality of every individual anticipated humanist and liberal ideals that would come to define the best of Western cultural aspirations hundreds of years later.

Their commitment to equality and truth led to Quakers’ persecution. It also led them to protest war and fight against poverty, to be abolishionists, anti-racists and peacemakers, as well as environmental activists and advocates for social justice and human rights, and early supporters of same-sex marriage and LGBTQ+ rights. While other religious institutions historically have been complicit in some of Western civilisation’s worst transgressions and a contributing force for maintaining repressive traditions, Quakers have consistently been among the first to stand up against societal injustice. Though not immune to the systems and culture of their time, it is common to find Quakers amongst those voices on the right side of history, speaking truth to power and waging peace on behalf of the disempowered, dispossessed, oppressed and mistreated.

If you choose to attend Quaker Meeting, you may also find that the stillness is moving, and that it moves you towards a more integrated version of yourself, and towards working in solidarity for a more just and fair world.

It's my belief that the radical spirit at the heart of Quakerism doesn't in fact belong to Quakerism at all, but to the larger forces of Light that move through the universe spreading connection, cooperation and compassion. Quakers have merely found a way of reaching that Light and allowing it to guide them. But as a Quaker, I don't intend on telling you what you should believe. My hope is that you won't take my word for it, but come to Quaker Meeting, avail yourself of this tradition, and be moved by the stillness yourself.

Sean Jacke – Hampstead Quaker Meeting